My mother has no idea what I do all day. Back when I was in coursework she understood that I read books, went to class, talked about the books, and then wrote papers about the books. When I was preparing for my comprehensive exams she understood that I read all day and then took notes on what I read, and six months later she could relate to taking a really hard test. Now that I am working on the dissertation, though, it's less familiar. I've described the archives to her and, since my dad wrote a dissertation many years ago (which she typed), she knows that I'll be spending two years putting my deep thoughts into words. It's how I get to those deep thoughts that is less clear to her. And she is not alone. I think most people are under the impression that historians primarily spend their time writing, but I reckon it's about a 50/50 split between research and writing (though this might vary from scholar to scholar).

The most mentally intensive part of research is reading and taking notes on documents, and it's also the least visible part of the process of writing history. Everyone has their own style of note taking and does it a little differently, but there are a few fundamental points that a historian always tries to capture. To demonstrate, I will walk through some notes I took yesterday on the document displayed in the slideshow above. You can use "next" arrow or click on the thumbnail tiles at the bottom to follow along.

This article by Rabbi Mordecai S. Halpern, "Detroit--And the Elephant--And the Center Problem," was published in a special issue of the journal Conservative Judaism [screenshot 1]. "The Center and the Synagogue: A Symposium" was published in 1962 and featured articles by prominent American rabbis criticizing Jewish Community Centers. I found a copy of this special issue of Conservative Judaism in the records of the National Jewish Welfare Board at the Center for Jewish History. Several leaders in the Jewish Center movement, including the director of the 92nd St. Y, were also solicited by the journal to respond to these arguments and mount a defense of the JCC.

The "Symposium" issue resulted from a dust up the previous year, when Rabbi Harold Schulweis of Temple Beth Abraham in Oakland, California, published a critique of the JCC's emphasis on leisure time and recreation. He denounced the institution for not incorporating sufficient Jewish content into their programming and for distracting Jews away from the synagogue by offering basketball and contact bridge. My first note, then--after the date, author, and title [screenshot 2]--was to contextualize the document [screenshot 3]. In his second paragraph, Rabbi Halpern borrowed an analogy made by Rabbi Schulweis*, so the first thing I indicated in my notes was that Rabbi Halpern's intention was to bolster the argument made earlier by his colleague. I briefly explained the analogy so that my future self can quickly grasp the meaning (and searching through the preceding document). I then highlighted and summarized the two purposes of the article that Rabbi Halpern articulated. I made sure that my lead-off note would provide a brief overview of the article's argument and of its intention: to reinforce Rabbi Schulweis's critique of the Jewish Community Center as insufficiently Jewish by offering a case study of the Sabbath policy of the Jewish Center of Detroit.

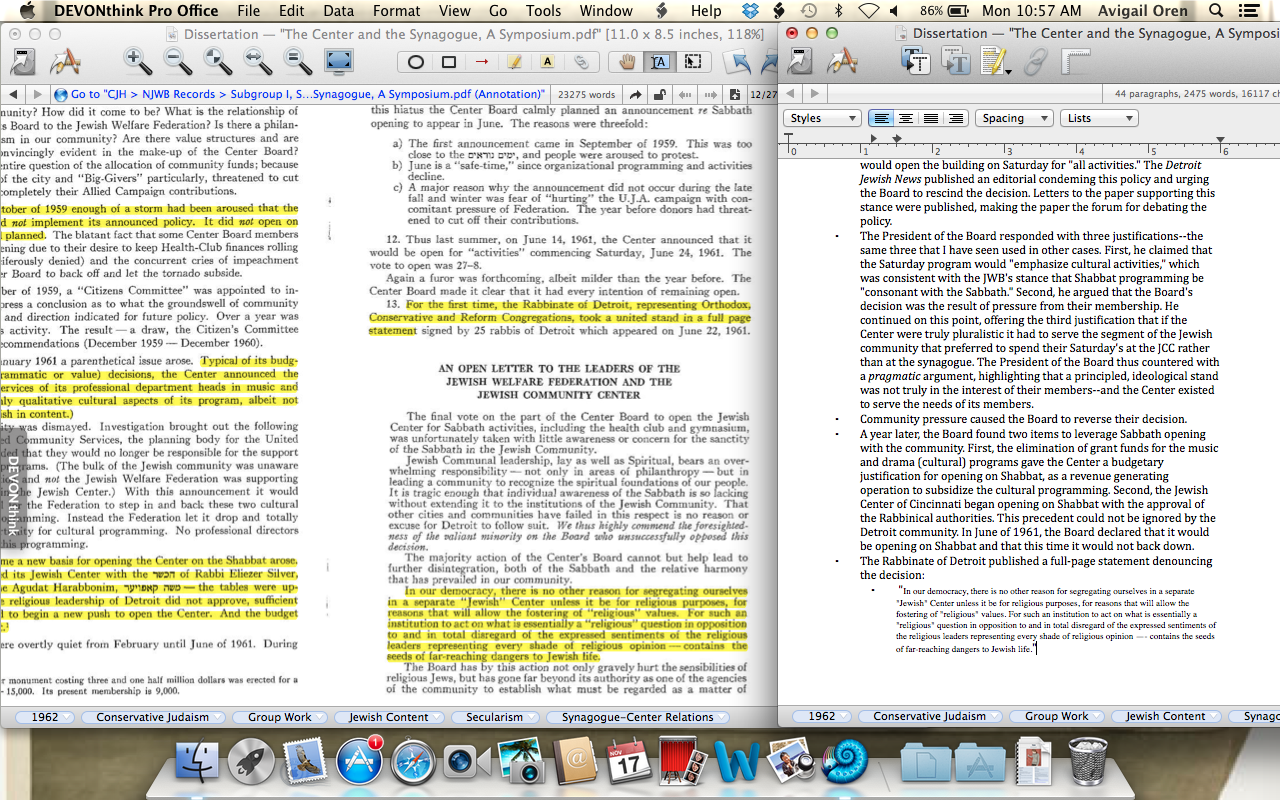

As I skimmed ahead, I realized that Rabbi Halpern organized his article into a chronological overview of the major events of the Sabbath policy debate between 1959 and 1961. Since my research does not deal with Detroit, I decided that it was not important for me to describe each detail of the debate. One of the Jewish Centers I am using as a case study, though, had its own battle with the rabbinate over Sabbath policy. I decided it would be useful to summarize the arguments that each side deployed against each other to justify opening or closing the Center on Saturdays [screenshot 4]. Later I can then compare the Detroit case to New York and possibly make a claim that the experience of "my" Center represents the norm for urban JCCs across the United States.

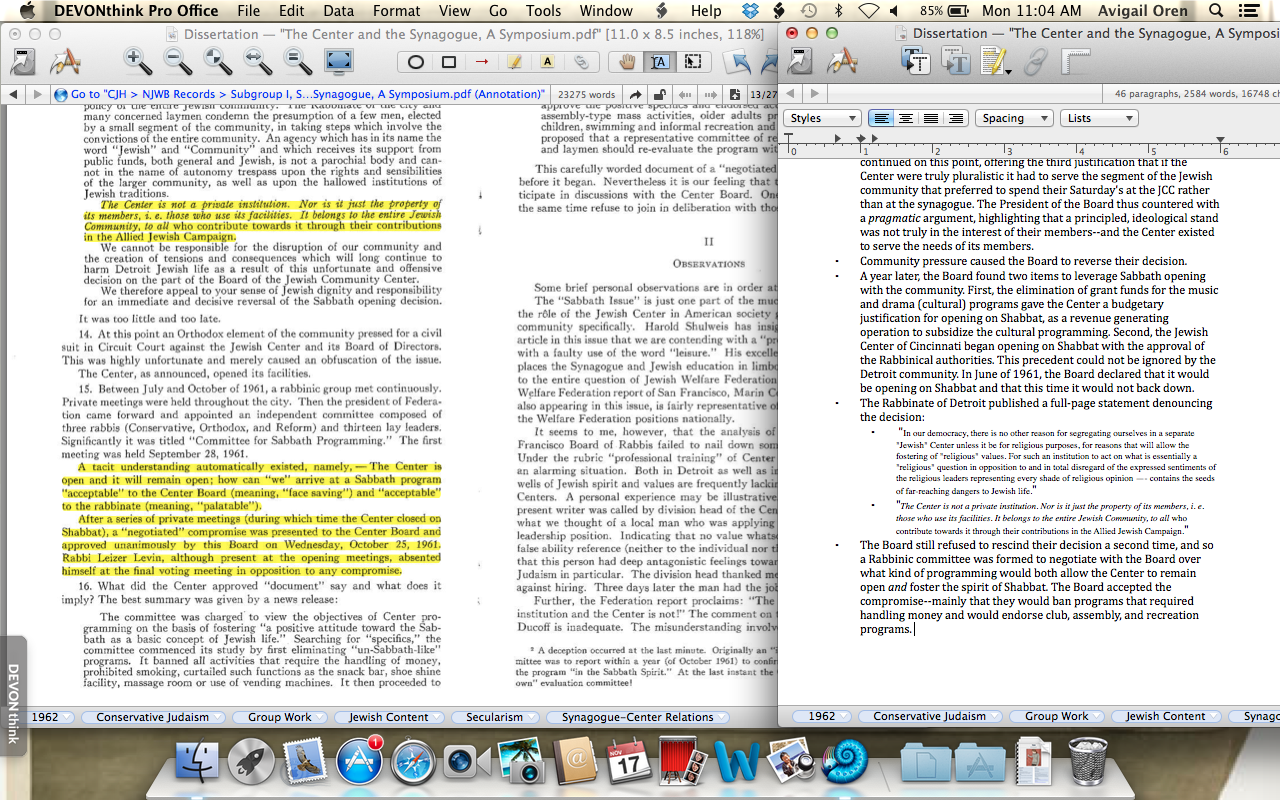

Next, I summarized how the debate ended. Essentially, the Center backed away from its plan to open on Saturdays after local rabbis and laypeople protested the desecration of the Sabbath by a Jewish agency. Historians are interested in change over time, so I made sure to note that the next year the Detroit Center again declared their intention to open on Shabbat [screenshot 5]. This time, they stood up to the rabbinate. Budgetary pressure provided them with leverage against their opponents. A major grantee withdrew financial support, leaving the Center to decide if they should cut their cultural program (drama and music) or increase their revenue by opening on Saturday. Even the rabbinate disapproved of cutting all of the cultural programs, and "negotiated" that the Center's Saturday programming would reflect the spirit of Shabbat [screenshots 6, 7].

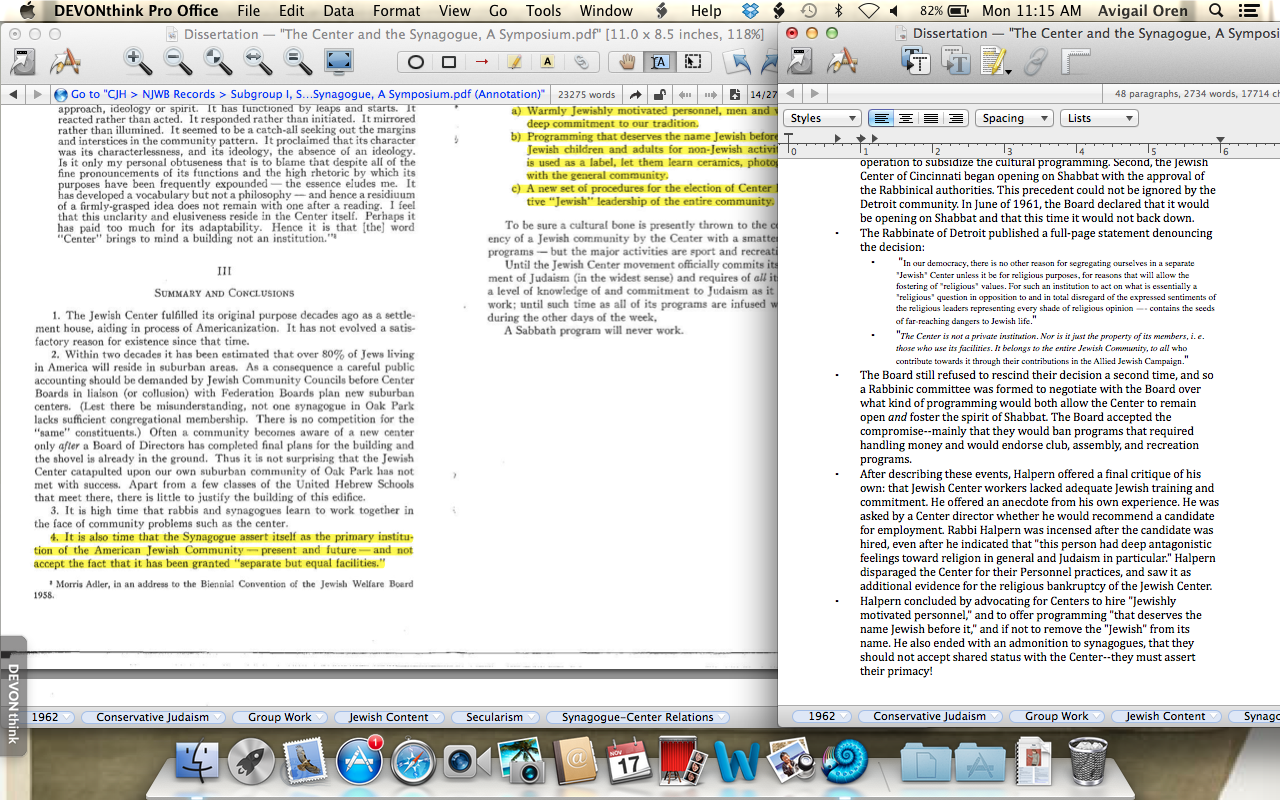

Rabbi Halpern concluded with a critique of his own. He argued that Jewish Center personnel lacked Jewish educations and that this inadequacy contributed to the insufficient Jewishness of Center programs. I noted this argument and the anecdotal evidence that Rabbi Halpern used as support [screenshot 8]. Finally, I finished my notes with an overall assessment of the document. I evaluated the relevance of the article to my dissertation--more specifically, how I plan to discuss the competition between synagogues and JCCs for limited membership and resources in postwar cities--and wrote a little reminder for my future self of how I think the article should be used [screenshot 9].

Effectively my notes are a distillation of the argument, intent and purpose, major points, and supporting evidence of a given document, paired with my evaluation of its relevance to my narrative. Most of my sources, however, are not articles. More commonly I am taking notes on organizational records: memos, letters, meeting minutes, reports, evaluations, or strategy papers. Sometimes there's no argument, only a laundry list of events or to-dos. Often, especially in memos and letters, the content is a director conveying their opinion to an employee they supervise. That leaves me with the unenviable task of interpreting the author's intent or their perspective on a topic. My point is, it's not always this explicit or clear. That's what keeps it interesting.

*Rabbi Harold Schulweis published a follow-up article in this special issue of Conservative Judaism. It is this article and not the original article in The American Rabbi that Rabbi Halpern is explicitly engaging.