One year ago, I launched a writing project on Patreon called Brisket. It was a home for essays I was writing that needed to be written “low and slow.” I recently sunset Brisket, and will be sharing the essays here on my blog throughout the coming months. This was the second piece, published in May 2018.

A few months ago, I was watching YouTube before bed when a new video by one of my favorite beauty vloggers, Shaaanxo, popped into my subscription feed. Shaanxo usually posts makeup tutorials and product reviews, videos that are about 10-20 minutes in length. Recording in a room of her New Zealand home that is entirely dedicated to storing her massive makeup collection, Shannon Harris turns on the camera and begins applying her makeup, chattily telling her 3.1 million subscribed viewers why she has chosen each primer, foundation, eyeshadow palette, bronzer, contour, powder, and lipstick to accomplish that specific look and giving her first impression on products she is using for the first time. She also does monthly roundups of her favorite new items, unboxing videos showing her viewers what the PR departments of makeup companies have sent her to try out, and vlogs about fashion, decor, and fitness.

This video, however, was different. First of all, it was almost an hour long. In it, Harris opened one of the massive drawers of what is best described as a custom-designed bureau—each drawer contains dividers specifically constructed to store lipsticks, or eyeshadow palettes, or pans of powder and blush and bronzer—and showed her viewers how overstuffed each one was. Then, after pulling out every item and piling it on the floor, she went through each one and selected what to keep, what to donate, and what to throw away. The keepers were lovingly rearranged back in the drawer, the rest relegated to a cardboard box to be taken to a local women’s shelter.

A decluttering video sounds like the most boring content that the social media ecosystem could ever create, like what reality TV would be if it was true to its name. But this new genre of programming is as alluring and popular as some of the smaller reality TV franchises, if not the Kardashians. A search for “decluttering” on YouTube in April 2018 returns 581,000 videos, though the videos are diversified across the categories of home design (organization and storage solutions) and fashion (closet purges) as well as beauty. Like this unreal, soapy genre, to watch a decluttering video requires no intellectual engagement whatsoever. They’re the perfect digestivo after a mentally and physically taxing day. Both mediums also prize beauty. Whether it’s the tanned, glam talent and elegant homes on TV or YouTube videos of colorful makeup in decorative packaging, the emphasis is placed on aesthetics. If they’re so alike, however, why wouldn’t viewers just defer to HGTV and Bravo? Why are they flocking to YouTube, and why to decluttering videos in particular?

While some of us were off watching Mad Men, The Americans, Game of Thrones, and the other premier shows that have characterized this “golden age of television,” YouTube quietly grew. From its founding in 2005, the site developed multitudinous ecosystems devoted to every interest and hobby as users uploaded new videos and learned how to build (and monetize) communities of like-minded enthusiasts. This became the hallmark of YouTube: consistent new and niche content. In just twelve years, the platform has grown to 1.5 billion global viewers—and it’s projected to reach 1.86 billion by 2021. By comparison, Netflix reported a record 117.6 million subscribers at the end of 2017. One billion hours of YouTube are watched daily.

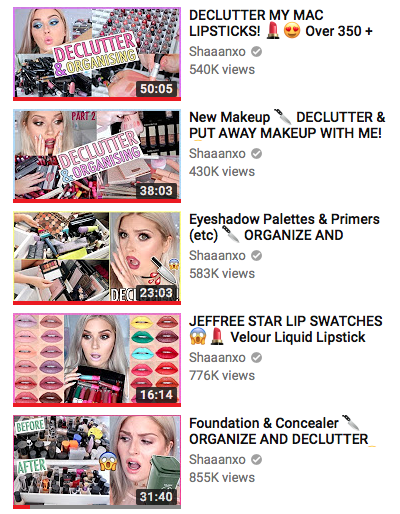

Many of those hours have accrued to Shaanxo’s makeup decluttering videos. She has the most-viewed decluttering video on YouTube, with 2.3 million views for the video in which she sorts through 1,000 lipsticks. In fact, of the 10 most-watched decluttering videos, five of them are from Shaanxo’s channel. [1] While other beauty YouTubers have created their own copycat content—trying to take advantage of how YouTube’s “suggested videos” algorithm rewards content tagged with trending keywords—the other five videos reflect the variety of the genre. Three focus on decluttering homes more generally, and three are by women who market themselves as experts in the field: Marie Kondo, Melissa Maker (@cleanmyspace), and Alejandra Costello (@alejandra.tv). [2] Focusing on the most- viewed videos, however, obscures the many content creators with fewer (but loyal) subscribers.

Clutterbug is one of the mid-size players on YouTube, with only 278,000 subscribers, but the channel has three videos that have garnered over one million views (and three more with over half a million views). [3] Like Melissa Maker and Alejandra Costello, Cassandra Aarssen also built a business around decluttering. She has published books and produces a podcast, in addition to blogging and running her YouTube channel. The Canadian mother of three developed a system to categorize everyone into “bugs” according to how much visual clutter they can tolerate and how devoted they are to organizing systems—“crickets,” for example, hate visual clutter and love organizing systems, whereas “butterflies” like to be able to see all of their stuff and can’t really deal with complex organization systems. Her videos make reference to this variety in people’s styles, and she rejects out of hand that there is any one “right” way to keep your home organized.

Regardless, decluttering is a priority, and in October 2017 she did a 30-day decluttering challenge on her channel where she went through her entire home purging unnecessary items. These very short videos tackled one small space at a time, such as underneath the kitchen sink, and Aarssen offered suggestions for what to do with old flower vases (repurpose them to hold plastic bags until the next time you buy flowers) and the best type of storage containers to use in this particular cabinet (flexible ones that can fit between pipes). Aarssen ends her videos with personal stories, freely admitting her imperfections. Her followers’ comments alternate between references to her stories and remarks about home organization; it’s not uncommon to see a comment like "You have the best, crazy stories!” right above a solution for organizing leftovers (“I put a small post it note on the front of the left over bin with contents and date, a little clear tape over”). Her subscribers tell her that they find her “motivational” and an “inspiration.” “Awe, thank you for being so supportive,” Aarssen wrote in response to one such comment.

So while channels like Clutterbug’s have pragmatic value, fans of decluttering also use the comment threads of YouTube channels to connect with the creator and with one another, building the kind of differentiated, unique community made possible by social media. Unlike celebrities that fans can only connect with on the stars’ terms, content creators on YouTube, Instagram, and SnapChat in particular interact with fans in order to build their audiences. This intimacy fosters loyalty between subscribers and channels, to the point where we will even watch our favorite beauty vloggers sort through old bottles of face wash.

We are undeniably in a period obsessed with minimalism, organization, and cleaning. While women’s magazines likeGood Housekeeping and Real Simple have long specialized in articles about how to creatively store gift wrap in guest room closets, organization and minimalism have become a mainstream concern (albeit still a gendered one). On HGTV shows like Love it or List It and Tiny House Hunters, organization and storage is routinely the primary concern for designers and home buyers. Several of the design overhauls featured in the new Netflix season of Queer Eye centered on organizational solutions; the Fab Five also preach minimalism to their mentee-men, purging old clothes and possessions in favor of carefully curated closets. Americans watch Hoarders with fascination and disgust; it’s relieving to know that your house isn’t that bad, even if every closet is filled with sentimental junk.

Perhaps the best example of this phenomenon is Marie Kondo, creator of the KonMari method of decluttering. Kondo has sold 8 million books worldwide about how to purge the objects in your life that fail to “spark joy.” She published her first book, The Life- Changing Magic of Tidying Up, in Japan in 2011 and in the United States in 2014—where it spent 143 weeks on the New York Times bestseller list. Through her books, consulting company, and now an upcoming Netflix series, Kondo attempts to fundamentally change people’s relationship to their possessions. To “KonMari” is to deploy her distinctive method, a prescribed set of steps for how to evaluate each object in your home and decide whether it adds value to your life or contributes to your happiness. What makes the KonMari method so attractive is this union of prescription and promise. Kondo recognizes that you’re overwhelmed, assures you that you will be happier with less, and then commands you to start sorting through your clothes (then books, paper, and miscellany, before finally tackling the sentimental).

Why have organization and minimalism become a mainstream concern now? What is it about the 2010s that inspired this efflorescence of tidying? The recession tightened Americans’ belts—specifically, it left millennials with student debt, smaller incomes, and a preference for experiences over stuff. That explains why some Americans are buying less, buying more mindfully, and living in smaller homes with fewer things. It is an unsatisfying answer, however, for why people feel compelled to purge belongings they already own.

Since the recession, paid work has become more precarious and insecure. [4] According to a Marketplace Edison Research poll conducted in February 2018, although economic anxiety is on the decline generally, certain segments of the American workforce remain wary of the future. The poll found that workers in the gig economy, as well as “African-Americans, women and 25-34 year-olds are the most anxious about their personal economic situations.” [5] Eleven percent of Americans now work full-time as independent contractors and a quarter of the American workforce participates in the gig economy. For these workers especially, control is something that can more readily be exercised at home than at work. A woman I am friendly with, who runs a communications consulting business, told me that decluttering “feels like the one thing I can and should be in control of with everything else out of control. I don’t know when I will get paid next, if I will have work next week/month/year, I don’t know how much the pay will be if I get it, I can’t plan for my future, I can’t control my health, I can’t control my pets’ health, nothing.”

And that’s what Marie Kondo promises: the chaos of clutter can be controlled. You may be losing sleep over whether you’ll lose your job, or the country will go through another recession, or you’ll land a new contract and if so when you’ll next get paid, but most of this is beyond your immediate control. You can, however, control your closet. By taking control of the chaos of your home, Kondo argues you will have more time to spend using the things you love, ultimately making you happier. Fewer possessions means fewer items going missing and less guilt over expensive purchases sitting there unused (a guitar for me, an elliptical for you). Consequently, taking time to declutter is an act of self-care.

Minimalism—an unselfish, ethical approach to consumerism—feels virtuous and altruistic in comparison to other forms of self-care, such as spa days or retail therapy, that seem to only benefit yourself. Despite a booming market for health, wellness, and beauty products and services, I regularly hear people justifying the time and money they spend on themselves—there needs to be a reason that one “deserves” self care. [6] A close friend describes how, at a weekly meeting where snack is served, the women in the office routinely say a variation of “I worked hard today,” or “I’ve been eating really healthy,” as they pick up small pieces of chocolate and place them on their plate next to cut vegetables and gluten-free pretzels.

In his 2005 book Born Losers, historian Scott Sandage explained how Americans’ understanding of failure evolved over the course of the nineteenth century; whereas in 1800 failure meant your business went broke, by 1900 it described your own personal failing to be ambitious and strive for something bigger. “Ours is an ideology of achieved identity,” Sandage wrote, “obligatory striving is its method, and failure and success are its outcomes.” He explains:

We do this because a century and a half ago we embraced business as the dominant model for our outer and inner lives. ... We reckon our incomes once a year but audit ourselves daily, by standards of long forgotten origin. Who thinks of the old counting house when we take stock of how we “spend” our lives, take “credit” for our gains, or try not to end up “third rate” or “good for nothing”? Someday, we hope, the “bottom line” will show that we “amount to something.” By this kind of talk we “balance” our whole lives, not just our accounts. [7]

There is no “obligatory striving” when you sit in a spa luxuriating. Although your muscles may relax, it cannot calm the anxiety that the time could be better spent pursuing grander ambitions. So we gravitate towards activities like decluttering, a form of self care that needs no justification—it’s hard work that demonstrates our striving towards the big goals of “zero distraction,” “maximum efficiency,” and “minimal waste.”

But it’s one thing to declutter your own home, and another to watch someone else do it. If we accept that people are obsessed with decluttering, it makes sense that they would be interested in watching people do it well. That explains the rising popularity of HGTV, and the general obsession with competence porn. Certainly there are some tips and tricks to be learned from observing how other people clean. Another explanation might be that people vicariously feel virtuous after watching someone else clean. If after a long workday you cannot muster the energy to reorganize a closet, but still feel a compulsive need to exercise control over disorder in a way you could not while at work, isn’t the next best thing to watch someone else do it? But these factors alone cannot explain why 581,000 videos on the subject have been created. Clearly, YouTubers have realized that a large audience exists and that these viewers are willing to watch multiple videos of people purging their possessions.

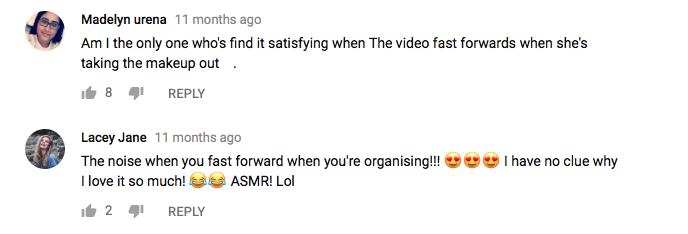

Over half a million decluttering videos exist partly because viewers use them to relax and fall asleep. Viewers commenting on Shaanxo’s decluttering videos describe them as “soothing,” “satisfying,” and “relaxing,” and I personally share this assessment. After watching Shannon purge liquid lipsticks from a giant drawer for 40 minutes, I feel purged of shpilkes (a great Yiddish word meaning nervous energy or restlessness). There is actually a phenomenological explanation for why these videos relax people: Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response, or ASMR. For those unfamiliar with ASMR, it describes a sensation of tingling that radiates from the scalp down the neck and arms that is triggered by sounds like whispering, tapping, and swishing water. Not everyone experiences “the tingles,” as they are referred to in internet parlance, and not everyone experiences them in the same way and as the result of the same stimuli. Even for people who do not experience the tingling sensation, however, these triggers induce relaxation.

If ASMR sounds made up, that’s because to some extent it is. The term was coined in 2010 by an active participant in online forums about the phenomena (after earlier proposals didn’t stick, including Attention Induced Head Orgasm and Attention Induced Observant Euphoria). According to Dr. Craig Richard, a professor of biopharmaceutical sciences and author-creator of ASMR University, discussion of the phenomenon originated in an online forum in 2007 when a commenter asked for an explanation of the sensation she had “as a child while watching a puppet show and when i was being read a story to” and “as a teenager when a classmate did me a favor and when a friend drew on the palm of my hand with markers.” Subsequent commenters could not explain it, but shared their own experiences with what would come to be called ASMR. Between 2008 and 2011, a subculture developed on Yahoo Groups, Facebook, Reddit, YouTube, and blogs as people, searching for explanations, found one another and began to share sources for “the tingles”—old episodes of Bob Ross, random videos on YouTube of people whispering, makeup tutorials, and unboxing videos. In 2009 the first YouTube channel dedicated to ASMR was created, but it took another three years for the genre to really blow up on the platform; Richards estimates that at least 60 new ASMR YouTube channels were established in 2012, eclipsing the 40 ASMR channels that existed in 2011. A search in mid-April of 2018 reveals that there are currently over 12 million ASMR videos on YouTube.

Unsurprisingly considering its grassroots origins, little scientific research has been done on ASMR; there’s scarce evidence to contradict the prevalent perceptions that ASMR is fake, exaggerated, or sexual in nature. According to a cursory search of PubMed, only five peer-reviewed studies attempting to explain ASMR have been published since 2015, though on ASMR University Richards also catalogues several studies that are in progress. When read together, the findings from these few research projects seem to indicate that the relaxing sensation of ASMR is the product of a heightened ability to imagine connecting with another person. Recent survey findings from a British team confirmed that those who experience ASMR are consistent in how they describe the sensation, about when and why they watch (at night, to relax and fall asleep), and their preferred triggers (whispering, personal attention, and slow, repetitive movements). A Canadian fMRI study comparing 11 people who experience ASMR to 11 controls found that the ASMR group had lower functional connectivity in certain areas of the brain as compared to the controls—the same areas of the brain were active in both groups, but in the control group those areas talked to each other more. This structural difference, the researchers hypothesize, may mean that people who experience ASMR have a “reduced ability to inhibit sensory-emotional experiences that are suppressed in most individuals.” This finding jibes with two other survey- based studies that found that participants who experience ASMR scored higher than control groups on the personality trait of “openness to experience” and the empathy trait of “fantasizing,” or the ease with which one becomes immersed in a story.

Finally, Richards has put forward the hypothesis (but not in a peer-reviewed publication) that, “Triggers that stimulate ASMR in individuals may actually be activating the biological pathways of inter-personal bonding. ... Some of the basic biology of bonding is well established and this involves specific behaviors which stimulate the release of endorphins, dopamine, oxytocin, and serotonin. These bonding behaviors and molecules may provide a good explanation for most of the triggers and responses associated with ASMR.” This is consistent with the centrality of personal attention in ASMR audio and videos (“ASMR art”), which is done to evoke the tingles and relaxation. One ASMR artist (ASMRtist) on YouTube describes first discovering ASMR as a young child. While watching a classmate coloring she was overwhelmed with a feeling of relaxation and felt the tingles because she felt certain the drawing was being made for her. Most ASMR videos are a form of role play, where the ASMRtist pretends to give you a haircut, or a spa treatment, or draw your portrait. They can get pretty out there, such as the Yeti Hair Salon video by ASMR Latte—a Korean ASMRtist who generally films more conventional videos but must be running out of generic concepts. You feel silly watching it, playing along as a yeti who needs its full-body coat of hair detangled, but the effect of the brushing sounds and the whispering is undeniably relaxing. I have always loved having my hair washed and brushed before getting a haircut, and it’s amazing how you can have the same physical response from simply imagining the sensation.

Decluttering videos include many traditional ASMR triggers— personal attention, tapping, soft voices and non-stimulating conversation—and so viewers are watching these videos to help them fall asleep. In the makeup decluttering videos on Shaanxo’s channel, Shannon positions the camera so you feel like you are sitting on the floor with her—a supportive friend willing to listen to why one color or formula is more favorable than another. The tapping sounds are made when Shannon empties her drawers and, post purge, reorganizes the items she keeps. When sped up—because usually these slower parts are fast-fowarded in the editing phase, to prevent the videos from being hours long—the clicks and clacks of the makeup bottles and tubes knocking into one another produces a tapping noise that reminds me of rain sticks or speed skates hitting the ice.

Fans of Shaaanxo’s channel, who come for beauty content not ASMR, comment with surprise that they’ve found the videos relaxing; without intending to do so, Shannon created videos that people were watching to relax. While not the most popular of her content—only one video of the 19 from her decluttering series, a lipstick purge that garnered 2.3 million views, is in the top 12 most-watched videos on her channel— decluttering videos are popular enough to encourage her, and many other beauty YouTubers, to keep making them.

The large and active communities and subcultures on YouTube put to bed the myth that the internet and smartphones have reshaped us into a society of unsociable, disengaged, and egocentric people—though internet subcultures certainly underscore that social bubbles and vacuums are strong. But YouTube also reveals that demand exists for a media ecosystem devoted to quelling anxiety, asserting control, and feeling virtuous. That’s what decluttering videos offer that reality TV does not. They’re as unintellectual and aesthetically- minded as the Kardashians, but they also offer connection to the content creator and a community of commenters, a way to engage in decluttering vicariously and find catharsis in someone else’s ability to control their environment, and, finally, a sensation of calm.

Ultimately, in watching these videos, people are doing themselves a kindness. No one is really learning anything from them (or rarely). There’s really very little to analyze, even if you have strong opinions about the items being decluttered. It reminds me of vacationing at a friend’s house, when they have some minimal obligation to keep up with the demands of their own life but you have the luxury of sitting on the couch without responsibilities, enjoying and providing company to a dear person. In those moments, you’ll happily listen to them prattle on about how they can never find anything in their kitchen junk drawer or watch them spend five minutes trying to find new batteries for the remote. Your job is to relax and not get in the way, to provide conversation while making yourself usefully useless. Watching a decluttering video takes this luxury one step further—you get to listen but never have the pressure of responding.

[1] Using the search term “decluttering.”

[2] Unsurprisingly, the creators and viewers of these videos are overwhelmingly women. A search for “decluttering men” returns only 8,000 videos. A quick scan reveals that many of these videos are made by wives decluttering their husbands’ closets.

[3] She is equally in the decoration and home organization space, which is why her most-viewed videos do not appear in the top 10 decluttering videos.

[4] Between 2005 and 2015, the number of Americans with “alternative work arrangements” or engaged in contingent work grew by 50%, from 10.5 to 15.8 percent.

[6] Case in point: In the “Pawnee Rangers” episode of the NBC comedy Parks and Rec, which originally aired on October 13, 2011, municipal workers Tom Haverford (Aziz Ansari) and Donna Meagle (Retta) devote a whole day to “treat yo self,” their annual tradition of taking the day off to buy thing for themselves without justifying why, so long as it makes them happy.

[7] Scott Sandage, Born Losers: A History of Failure in America, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2005), 264-5.