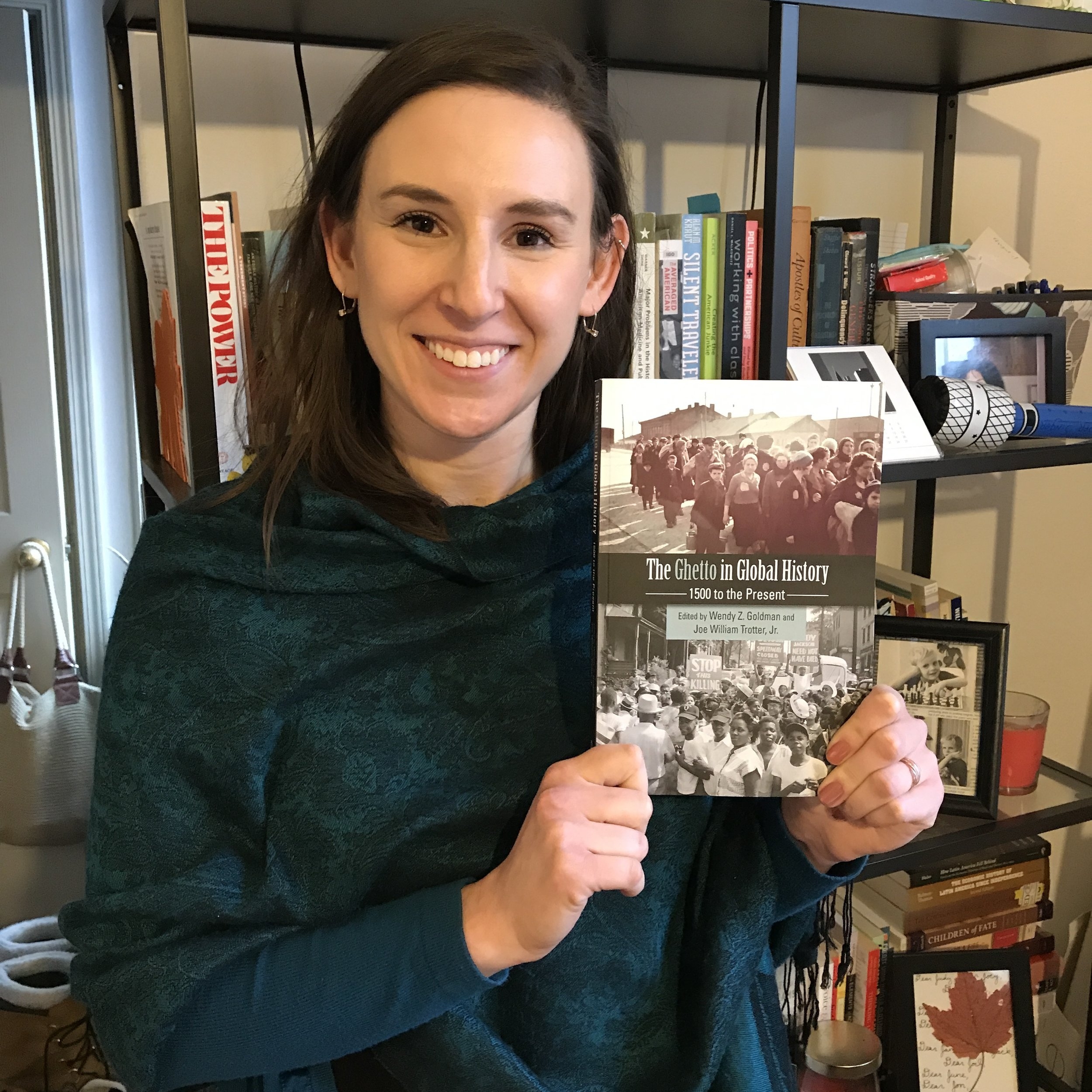

They say that it only takes two things to be a writer: to write, and to call yourself a writer. But I can now tell you that there is an undeniable joy and pride that comes from seeing your work printed in a book. A book that two very senior scholars had the idea to write, and asked me if I would contribute a chapter to it. And when I said yes, they then read and carefully edited my words and tightened my argument, and then sent it to the UK where a person agreed it was worth publishing and spent a lot of time and energy laying it out in a fancy book-printing computer program, and then sent to a big book-making factory and had it bound up. And now it costs $53.70 on Amazon and is ranked #1,428,714 on the site's best seller list (but is boosted up to #1416 in books about African American history).

I was working from my dining room table yesterday afternoon when my husband came home and brought in the mail. After weeks of waiting, the book had finally arrived--and I was in the middle of working and it had been a long, long day and I just threw up my hands and said "finally!" and went along with what I was doing. What was a little more waiting, at this point?

The chapter that I contributed to this book originated from a year-long seminar I participated in during the 2014-15 academic year. I began the research in the fall of 2015, completed a draft in August of 2016, and did three rounds of revision and submitted a final version by the end of that year. In the spring and summer of 2017 I made final edits and approved the page proofs. The book was finally released in December 2017, but a printing delay meant that my copy was not sent out until mid-March. And then it took three weeks to ship from the UK. If you had told me that I would not see the fruit of this labor for four years, I probably never would have done it. Yet that's fairly typical for academic publishing, and realistically it would have taken a fifth year if I had submitted it to a journal.

So I left the book sitting on the table while I finished working, ate dinner, and watched Sunday night's episode of Silicon Valley with Kevin (so good!). Before leaving to meet a friend to see Viet Than Nguyen speak, I scooped it up and threw it in my bag. We arrived early enough that I had time to show her before the event started. Her enthusiasm was contagious, and after she insisted on taking pictures of the book I began flipping through to find my chapter. You might be surprised to know which page made me verklempt.

I created this chart and table in Excel and I am not being self-deprecating when I say that the originals are amateurish and lacking in aesthetic merit. So when I opened to this page in the book, and found that they looked professional and "like what a chart in a book should look like," it drove home the point that I had actually done something legit.

So my eyes watered a little bit, though I did not actually cry, and I spent a few seconds saying something dumb like "wow, huh, wow" before pulling it together and changing the subject.

After the talk I came home and before I went to sleep I placed the book on the table next to my bed. When I got up this morning I put it in my bag and carried it around with me all day. This afternoon I brought it to show my therapist. But I think by tonight I'll be ready to find a nice home for it on a bookshelf.

I never was a kid who really knew what she wanted to be when she grew up, but I was always writing--journal entries, awful short stories and poems, school papers, personal essays, letters to friends, and later blogs, and newsletters, and a dissertation. So this book does not quite represent my actualization into the person I dreamed I could be. Instead, it underscores what I already know: I've become a writer.