Earlier this morning, my husband and my mother were in the kitchen strategizing about how to cook a brisket and bake almond macaroons at the same time. My husband patiently reviewed the detailed timeline he outlined two days ago--the gefilte fish out of the oven by 10 so the macaroons can get in and out by 11:30, when the vegetables go in, followed by the brisket and then the meatballs at 4:30. A few minutes later a storm rolled in, knocking out the power and forcing them to figure out how to continue without a functioning oven.

Over the past week, Kevin has read through recipes, consulted with my mom, written and revised shopping lists, visited two grocery stores and Bed, Bath, and Beyond, helped switch out the normal dishes for the Passover dishes, cleaned out the fridge and pantry, and cooked. This is what true love is: taking on the most labor-intensive holiday of your wife’s religion despite being an atheist. My family does this to feel connected to an ancestral tradition and to a global community. Kevin does this to feel connected to us.

* * *

Last night, we went out to Los Pollos for dinner with my parents. We sat at a picnic table on the restaurant’s porch, enjoying our last rice and beans before a week without bread, grains or legumes. My father fumbled with the ribs we had ordered, struggling to remove a serving for himself.

“Have you ever had ribs before?” Kevin asked.

“We had Chinese spareribs on our first date,” my mom recalled, “which almost didn’t happen because your father told me the wrong corner to meet him on, the southeast instead of the northeast. Then we saw Yentl, which your father hated.”

My father nodded in agreement.

“Abba,” I said, “tell me your version of how you and mom met. I’ve only heard the story from her perspective.”

“It was in December of 1983, at a Hanukkah party organized by and for Israelis at NYU. It was held at HUC [Hebrew Union College] in the West Village. I went with my friend Shaul…”

“Describe Shaul to them, Ido.”

“Shaul was also at NYU, writing a dissertation on dreams in the Hebrew bible. He was diminutive and dressed slickly.”

My mother interrupted. “I went with a friend, an occupational therapy student, who was short and I was tall. I convinced her that we should go over and dance and she started dancing with Shaul and I started dancing with your tall father.”

“Yes. We danced and then I asked her for her number. I didn’t have my cell phone so she couldn’t just type in her number. She had to write it down on paper.”

“Show them, Ido.”

I gasped. I had heard this story from mother so many times and never once did she indicate that any evidence remained.

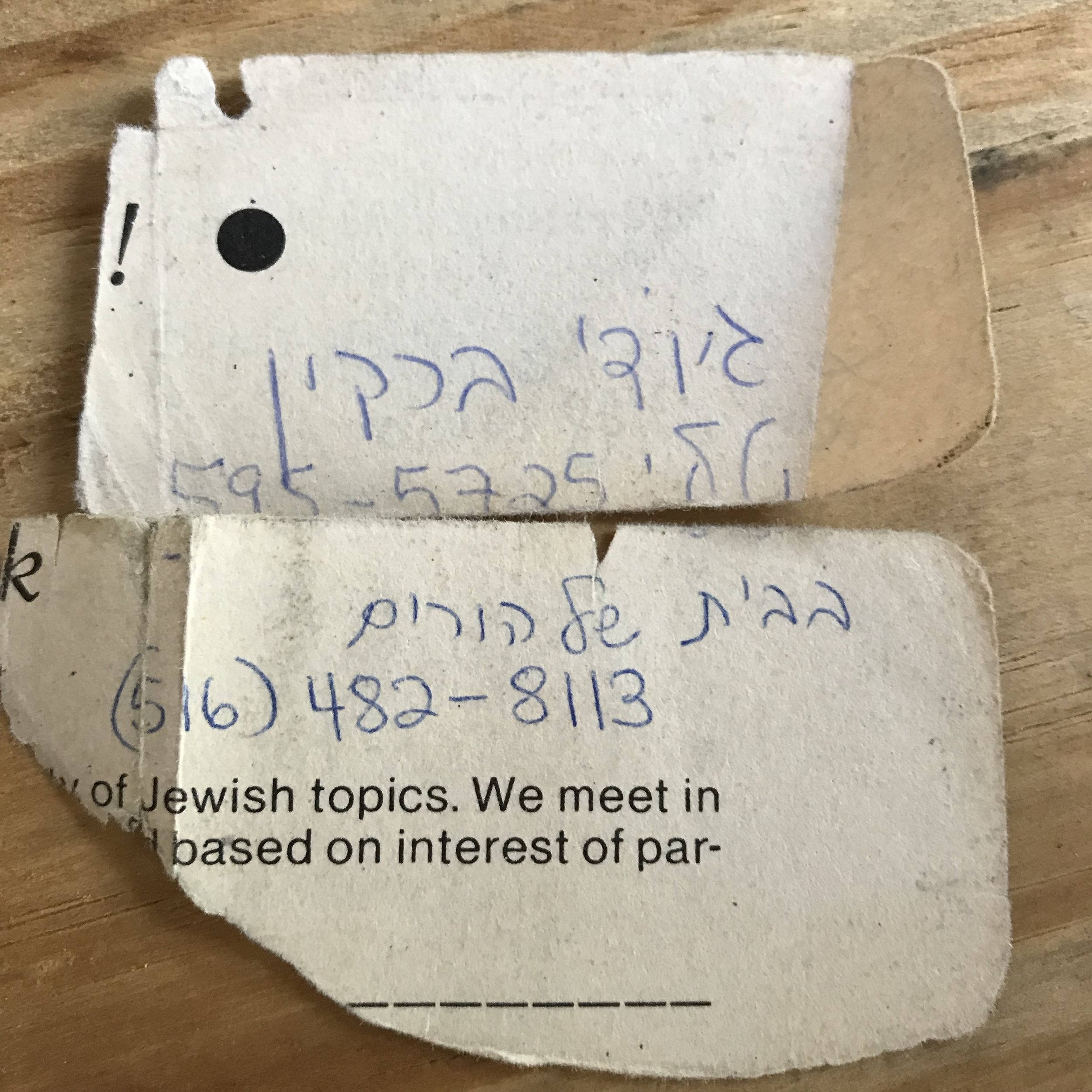

“It’s practically disintegrated.” Nevertheless, my father pulled out his wallet. Out of one of the smallest compartments he extracted the 35-year-old scrap of paper, in two pieces. In her familiar handwriting, but in Hebrew, she had written her name—Jodi Barkin—and two phone numbers, the one for her apartment and for her parent’s house on Long Island where she often spent the weekends. I flipped it over and found course listings for HUC seminars. They must have picked up whatever was on hand in the room.

My father called a few days later and asked my mother out to a Chinese restaurant at 97th and Broadway. By New Years they were living together in my mom’s studio apartment at 71st and Columbus. In December of 1984, one year after they met, my father proposed.

* * *

A few years ago I invited a friend to have lunch with me and my parents in Georgetown—I can’t remember why we were in D.C., but this friend lived there. It was her first time meeting my folks, and as we were leaving she turned to me and said, “your parents are so in love.” It took me by surprise, because although I knew my parents had a happy marriage and that they loved each other, I did not realize that it was evident (or of interest) to other people. It’s only now that I am older, having seen many unhappy and dysfunctional relationships, that I realize how lucky I am to have been able to take love like my parents’ for granted.

* * *

Love may seem like an awkward topic of reflection for a holiday that’s about freedom from the bondage of slavery, but I would argue that it’s the crux of freedom’s goodness. There is an anecdote in Te-Nehisi Coates’ Atlantic article “The Case for Reparations,” which I assign to my undergraduate students, that describes an enslaved man watching his wife and children sold away.

Every time I read this article, this line makes my chest squeeze and my breath hiccup. The image is so vivid, and if the situation is not relatable the sorrow of loss certainly is. Students always bring this anecdote up in discussion. Whereas the labor and economy of slavery is abstract to them, family, and love, is not. Liberation from slavery (whether in Egypt or the Americas) was not only motivated by love—the need for agency, autonomy, safety, equality, and power were also essential drivers—but it is my students’ visceral understanding of the former and their uneven experiences of the latter that provokes their empathy. Reading this anecdote, students come to understand that slavery is more than just a “bad” thing to do to other people; slavery is a personal terrorism of separation from, loss of, and grief for the people you love.

* * *

So I feel fortunate, on this holiday, for my freedom and the love that surrounds me. It is not to be taken for granted. It is a reminder to fight for a just world in which everyone shares the same freedom. For once we were slaves in Egypt.